Civil dialogue at the EU level: an introduction

Glossary

Non-profit Organisation (NPO)

NPOs are all those organisations that are neither for-profit companies nor state or local government public authorities. They are dedicated to the pursuit of objectives for the common good, with no primary objective of financial gain. Any secondary economic activities may be undertaken only to achieve the social or altruistic mission of the organisation, and profits may not be distributed among members.

Civil Society Organisation (CSO)

CSOs are a type of NPO covering diverse and independent organisations, networks, associations, public benefit foundations, groups, and movements that collaborate to advance shared goals through collective efforts.

Non-governmental Organisation (NGO)

NGOs, as part of CSOs, operate independently from public authorities. They serve as a bridge between citizens and politics. NGOs inform citizens about political developments, and empower or facilitate their political participation. In parallel, they point out central societal concerns to politicians. NGOs also provide services that respond to needs present in society, advocate for change, and act as watchdogs of the institutions.

Foundations

Public Benefit Foundations, a type of CSO, facilitate charitable activities by providing grants to organisations, institutions, or individuals for purposes such as science, education, culture, religion, and other causes. While grant-making is their primary focus, some foundations also directly participate in charitable initiatives or programmes.

Citizen

In the context of civil society, the term “citizen” is often used to refer to all inhabitants, irrespective of their legal status, including those in possession of a country’s citizenship, temporary or permanent residents, as well as the undocumented population.

Civil dialogue

Civil dialogue involves the exchange of views and information between civil society (organisations) and public authorities as part of the decision-making process. It can be initiated by either party and is characterised by regular, transparent, structured, and collaborative interactions.

Civic space

“Civic space is the environment that enables people and groups – or ‘civic space actors’ – to participate meaningfully in the political, economic, social and cultural life in their societies. Vibrant civic space requires an open, secure and safe environment that is free from all acts of intimidation, harassment and reprisals, whether online or offline” (UN Guidance Note on Protection and Promotion of Civic Space).

Exclusive competence

Area in which the EU alone is able to legislate and adopt binding acts.

Shared competence

Area in which both the EU and the Member States can adopt legally binding acts. The Member States can exercise that competence if the EU has not exercised it yet, or has decided not to.

Supportive competence

Area where the EU can only intervene to support, coordinate or complement the action of its Member States. Legally binding EU acts must not require the harmonisation of the laws or regulations of the Member States.

Ordinary legislative procedure

Main legislative procedure for EU lawmaking in which the European Parliament and the Council of the EU both need to approve a law and both are able to amend it.

Directive

An EU ‘framework law’ that requires specific laws by the Member States in order to be implemented and applicable.

Regulation

An EU law directly applicable to the whole of the Union.

Trilogue

Informal meetings between the European Parliament, the Commission and the Council over a legislative file to find an agreement between the Council and the Parliament on a common text to be submitted to the formal approval of both institutions. In the trilogues, the Commission acts as a mediator.

Content

- Glossary

- In what areas can the EU legislate, and to what degree?

- What are the main steps of the EU legislative process?

- The Commission is the only body that can propose laws

- What is the ‘civil dialogue’?

- What do the Treaties say about civil society?

- Is the European Commission implementing Article 11 of the Treaty on the European Union?

- What do the European Parliament, the Council of the EU and the European Council do to involve civil society?

- Recommendations

- To wrap up

- Take the quiz!

- Materials and resources

Expected learning outcomes

- To explain the three types of competences of the EU: exclusive, shared, supportive.

- To explain the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure in broad terms.

- To explain what the term ‘civil dialogue’ means.

- To explain what the EU Treaties say about civil society involvement in policy-making.

- To explain what the ‘Better regulation’ communication entails for civil society organisations.

- To explain in broad terms the involvement of civil society organisations in the work of the European Parliament, the Council of the EU and the European Council.

In what areas can the EU legislate, and to what degree?

The EU can adopt legally binding acts on a specific number of areas, defined in Title I of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU, art. 2-6): where the Treaties do not give the Union any role; that area is left to the Member States. The EU can act on different areas based on three types of competences:

- Exclusive competences: areas in which the EU alone is able to legislate and adopt binding acts. The areas under exclusive competences are very limited, and include the customs union, the monetary policy for euro-area countries, and the common commercial policies.

- Shared competences: areas in which both the EU and the Member States can adopt legally binding acts. The Member States can exercise that competence if the EU has not yet exercised it, or it has decided not to. They include a wide range of areas, including the environment, internal market, regional policy, energy, and some aspects of social policy.

- Supportive competence: areas where the EU can only intervene to support, coordinate or complement the action of its Member States. Legally binding EU acts must not require the harmonisation of the laws or regulations of the Member States. It includes areas such as industry, culture, education and tourism.

What are the main steps of the EU legislative process?

There are two main types of European laws:

- Directives, EU ‘framework laws’ that require specific laws by the Member States in order to be implemented and applicable.

- Regulations, EU laws directly applicable in the whole of the Union.

The Commission is the only body that can propose laws

The European Union has several legislative procedures (for a full overview, see EU Monitor). The main one is the ordinary legislative procedure, which is the one used unless the Treaties specify a different procedure. Its main characteristic is that both the European Parliament and the Council of the EU equally have to approve the law, and can propose amendments to it. While both the Council and the Parliament start examining the text at the same time, formally the first to vote on a text is the European Parliament, while the Council votes on the amended text. If the Council amends the proposal, the new version is sent to the Parliament for a second reading. If the Parliament amends the Council’s proposal, the new text is sent to the Council and to the Commission, which gives its opinion on it. If the Council does not approve all of the Parliament’s amendments, a Conciliation Committee composed of an equal number of Council and Parliament representatives is established to reach an agreement on a common text, with the mediation of the European Commission. This final text is sent to both the Parliament and Council for a third reading. In practice, very few legislative proposals arrive at the Conciliation stage, as once the initial positions of each body are clear, the Commission, the Parliament and the Council organise informal negotiations called trilogues to reach a common text, therefore anticipating the practice of Conciliation to earlier stages of the process.

What is the ‘civil dialogue’?

While no legal definition exists at the EU level on what ‘civil dialogue’ is, a practical definition of it has emerged over the years as ‘civil society’s engagement in the entire cycle of EU law- and policymaking, not only on specific thematic areas throughout the policy cycle, but also on programmatic issues and agenda-setting’. More specifically, the European Economic and Social Committee has identified three complementary forms of civil dialogue:

- Vertical dialogue: sectoral civil dialogue between civil society organisations and their interlocutors within the legislative and executive authorities.

- Transversal dialogue: structured and regular dialogue between EU institutions and all of these civil society components.

- Horizontal dialogue: dialogue between civil society organisations themselves on the development of the European Union and its policies.

What do the Treaties say about civil society?

The Treaty on European Union – TEU and the Treaty on Functioning of the European Union – TFEU (usually called ‘the Treaties’) function as a de facto constitution for the European Union. In the Treaties, civil society is mentioned in four articles: Art. 15, 300, 302 of the TFEU and Art. 11 of the TEU, in the section on democratic principles.

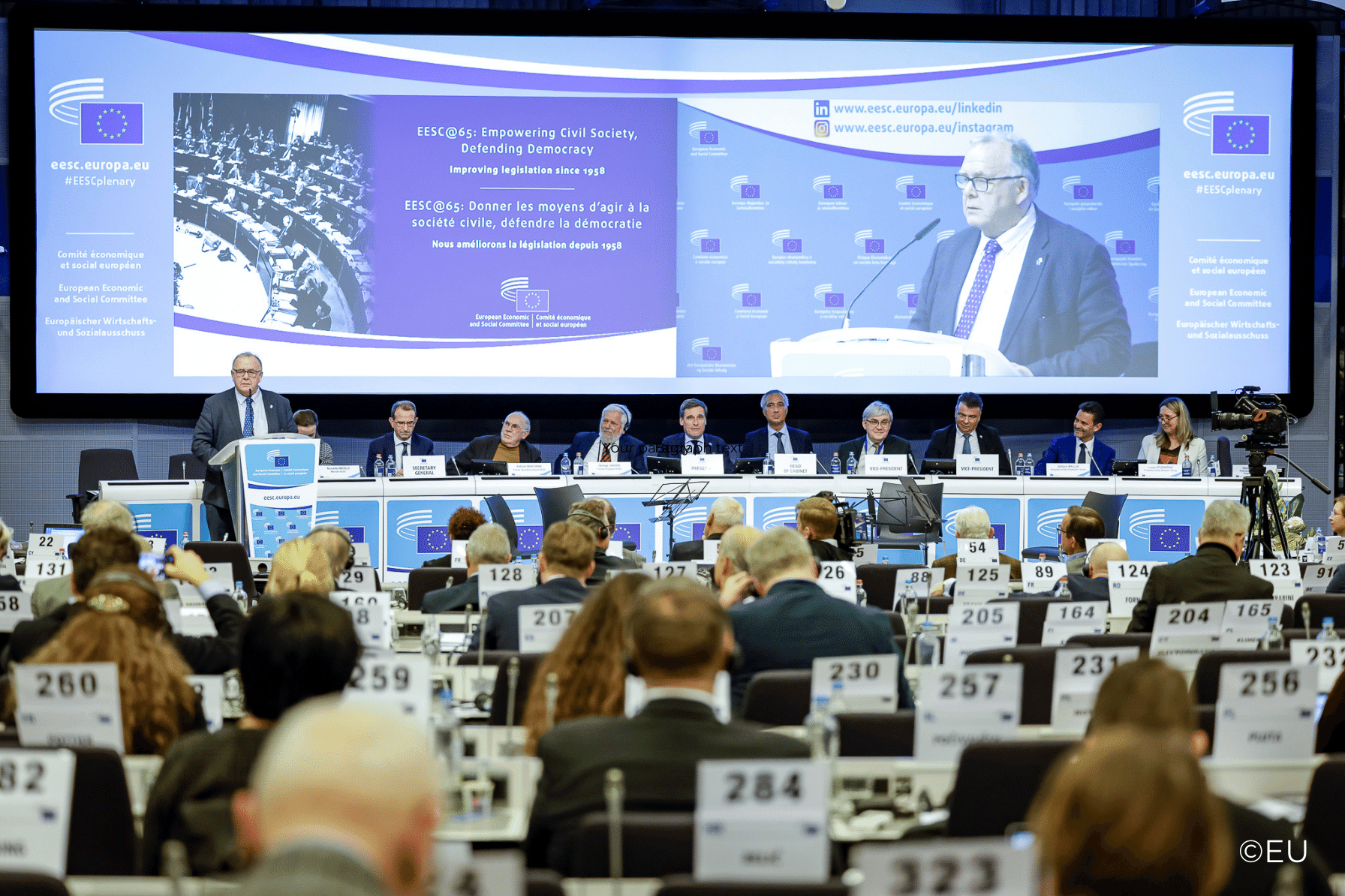

Art. 15 of the TFEU establishes the duty of transparency for the European institutions, in order to promote good governance and ensure the participation of civil society (see section ‘Transparency in EU institutions’). Art. 300 of the TFEU deals with the composition of the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), which is made of representatives of organisations of employers (Group I), of the employed (Group II), and of other parties representative of civil society, notably in socio-economic, civic, professional and cultural areas (Group III).

Art. 302 of the TFEU indicates that the Council appoints the members of the EESC proposed by the Member States, after consulting the Commission; but also that the Council can also ask for the opinion of European bodies —which are representative of the various economic and social sectors— and of civil society; however, such a review is felt as merely formal by some European CSOs, which have managed to influence the appointment process only in very limited cases.

Art. 11.2 of the TEU deals with the citizens’ participation in the EU policy-making processes. In particular, it says that the institutions shall maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society. While not mentioned explicitly, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) consider this article as the legal foundation for the establishment of civil dialogue mechanisms at the EU level. They therefore call for the implementation of Article 11 of the Treaty on European Union.

While not mentioning civil society directly, other articles of the EU Treaties (or of texts that have the same value as Treaties) concern civil society: Art. 10 of the TEU describes the functioning of the democracy at the Union level, and recognises that ‘every citizen shall have the right to participate in the democratic life of the Union. Decisions shall be taken as openly and as closely as possible to the citizen’ (Art. 10.2). The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which is at the same level as the Treaties, but applies only when implementing EU law, guarantees several freedoms linked to the operations of civil society, such as freedom of expression and information (Art. 11), freedom of assembly and association (Art. 12), right to good administration (Art. 41), right of access to documents (Art. 42), right to refer to an Ombudsman (Art. 43), right to petition (Art. 44).

Is the European Commission implementing article 11 of the Treaty on the European Union?

A legislative provision that implements Article 11 does not exist, as the article itself does not provide a specific obligation to act. However, the Commission has adopted a new communication to the other institutions called ‘Better Regulation: Joining forces to make better laws’. In this communication, in the complementary staff working document and in the toolbox, the Commission identifies public consultations via the Have your say portal as the main way to gather input from citizens and stakeholders, while targeted consultations with stakeholders are preferred when the subject is deemed too technical or of limited interest for the general public (see section ‘Civil Dialogue: the European Commission’).

What do the European Parliament, the Council of the EU and the European Council do to involve civil society?

The European Parliament has a Vice-President in charge of organising consultations with civil society organisations. CSOs are also invited to hearings by the Parliament committees. Citizens, also on behalf of CSOs, can petition the Parliament on a subject which comes within the European Union’s fields of activity that affects them directly, and has a committee specifically dedicated to examining them (see section ‘Civil dialogue: the European Parliament’). The Council of the European Union (also called ‘the Council’) does not have a framework of engagement with CSOs, apart from the field of foreign affairs. Any other CSO involvement is either based on the tradition of involvement of some organisations in the informal sectoral Council meetings, or is decided on at the initiative of the rotating Presidencies of the Council. The European Council does not have any framework of engagement with civil society, apart from a general right to send letters to the institutions enshrined in the Treaties (see section ‘Civil dialogue: the Council of the European Union and the European Council’).

Recommendations

- Create an (inter-)institutional framework for a regular and structured civil dialogue spanning the entire policy cycle, involving pan-European CSOs in agenda-setting, drafting, implementation, and monitoring stages.

To wrap up

- The European Union can only legislate in areas assigned by the Treaties, and with a different degree of intensity based on the division of competencies: exclusive competences (only the EU legislate), shared competences (Member States can legislate if the EU has not done so), supportive competences (the EU cannot legally produce harmonisation of laws and regulations in the Member States).

- In the ordinary legislative procedure, Parliament and Council have the same right to amend the proposals, and both have to approve the same text.

- Civil dialogue means systemic involvement of civil society in all the stages of policy-making.

- Civil dialogue is not codified by the EU legislation, but its basis is considered to be Article 11 of the Treaty on European Union.

- The Commission’s guidelines for the citizens’ engagement in policy-making are in the ‘Better regulation’ communication, which establishes public consultations as the main way to gather the input of citizens and stakeholders.

- The European Parliament has several ways to involve civil society organisations, as well as a specific right to petition.

- The Council of the EU and the European Council have no systematic framework of involvement for civil society, and it is up to the individuals’ initiative.

Materials and resources

- EnTrust (2023). Report on practices of enhanced trust in governance

- European Commission (2023): Recommendation on promoting the engagement and effective participation of citizens and civil society organisations in public policy-making processes

- European Commission (2023): Better Regulation Toolbox.

- Council of the EU (2023). Conclusions on the application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights; The role of the civic space in protecting and promoting fundamental rights in the EU

- European Civic Forum & Civic Space Watch (2022). Towards vibrant European civic and democratic space.

- European Parliament resolution (2022) on Shrinking space for civil society in Europe

- European Civic Forum & Civil Society Europe (2021). Towards an open, transparent, and structured EU civil dialogue.

- European Commission (2021). Better Regulation: Joining forces to make better laws.

- European Commission (2021). Better Regulation Guidelines.

- Council of the EU (2017). EU engagement with civil society in external relations – Council conclusions.

- Treaty on European Union (2012).

- Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (2012).

Project information

Project Type: Collaborative Project

Call: H2020 SC6 GOVERNANCE-01-2019: Trust in Governance

Start: February 2020

Duration: 48 Months

Coordinator: Prof. Dr. Christian Lahusen,

University of Siegen

Grant Agreement No: 870572

EU-funded Project Budget: € 2,978,151.25