Civil dialogue: the European Parliament

Glossary

Political group

The Members of the European Parliament are organised into transnational political groups. Political groups are formed by at least 23 MEPs from one-quarter of the Member States. MEPs not affiliated with a political group are called ‘non-attached (NI)’. Each political group takes care of its own internal organisation by appointing a chair (or two co-chairs, in the case of some groups), a bureau and a secretariat. Political Groups are crucial actors in the Parliament’s plenary, but also in the committees and delegations.

National delegation

In the context of the political groups, the national delegations are called the groupings of MEPs from the same national political party. They are led by a head of delegation. NB: in the same political group, there can be more than one party from the same country; in that case, they normally organise themselves separately.

Committee

The committees are official thematic subgroups of MEPs, composed of representatives of all the political groups and the non-attached members, preparing the policy and legislative proposals from the Commission to be discussed and voted on in the Plenary. They can also work on their own initiative resolutions or reports. The head of a committee is called ‘Committee Chair’, assisted by Vice Chairs from the other political groups.

Parliament Delegation

The Parliament Delegations are official subgroups of MEPs, representing all the political groups and the non-attached members, which maintain relations and exchange information with parliaments in non-EU countries.

Conference of Presidents

The Conference of Presidents is the political body of the Parliament that is responsible for the organisation of Parliament’s business and legislative planning, deciding the responsibilities and membership of committees and delegations, and relations with other EU institutions, the national parliaments and non-EU countries. It consists of the President of the European Parliament and the political group chairs. Non-attached MEPs have one seat, without the right to vote.

Rapporteur

In a committee, the rapporteur is the MEP in charge of preparing the policy file (legislative or non-legislative) for the Committee and presenting it to the Plenary.

Shadow rapporteur

In a committee, the shadow rapporteurs are MEPs appointed by their political group to be in charge of a particular file and negotiate with the rapporteur.

Coordinators

In a committee, the coordinators are the MEPs designated by their political group to coordinate the group’s work within the committee.

Intergroups

Intergroups are informal forums for informal exchanges of views on specific issues across different political groups, and contact between Members and civil society or stakeholders. Each is composed of Members from at least three different political groups.

Directive

An EU ‘framework law’ that requires specific laws by the Member States in order to be implemented and applicable.

Regulation

An EU law directly applicable to the whole of the Union.

Content

- Glossary

- How is the European Parliament structured?

- How does the European Parliament organise its decision-making process?

- What are the avenues of involvement for civil society in the decision-making of the Parliament?

-

How does the right to petition the Parliament work?

- Example of successful petition to the European Parliament

- Recommendations

- To wrap up

- Take the quiz!

- Materials and resources

Expected learning outcomes

- To be able to navigate through the structures of the European Parliament.

- To explain the policy-making process of the European Parliament.

- To enumerate the avenues of civil society involvement in the Parliament’s decision-making.

- To be able to send a petition to the European Parliament.

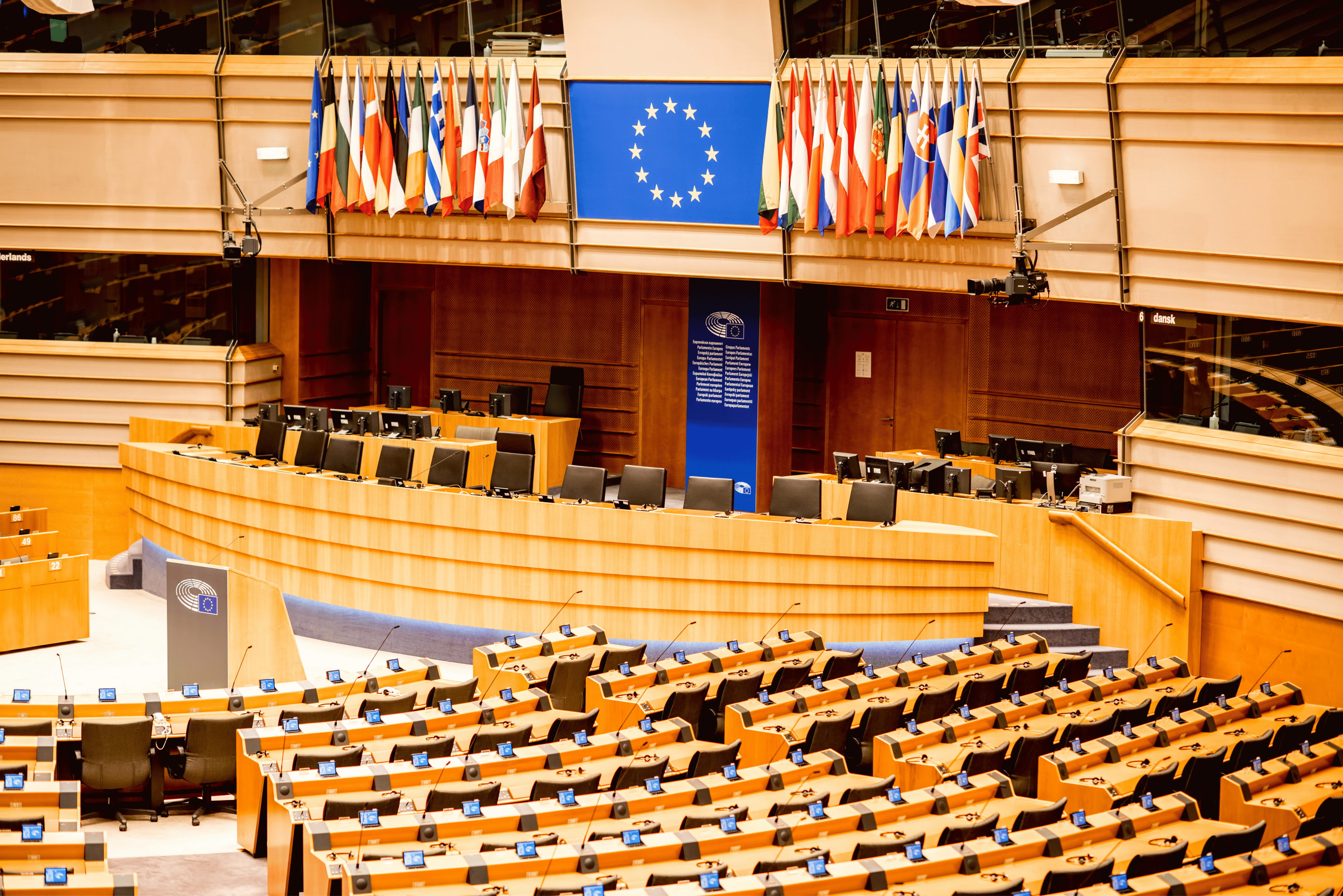

How is the European Parliament structured?

The European Parliament has a political side and an administrative side. On the political side, the Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) are the policy actors of the institution. Each MEP has one or more assistants (called APA, Accredited Parliamentary Assistant) that help them carry out their daily duties and provide support on content issues. They are organised around political groups, based on party affiliation (e.g., socialists, greens, liberals, Christian democrats, etc.), led by a chair (or two co-chairs, for some groups). In the Plenary, the Parliament elects its President, the Vice-Presidents and the Quaestors (responsible for administrative and financial matters directly concerning Members and their working conditions). The President and the chairs of the political groups (plus one representative for the non-attached MEPs, without the right to vote) form the Conference of Presidents, which plans the political work of the Parliament, while the Bureau, made of the President, the Vice-Presidents and the Quaestors, is responsible for all matters relating to the internal running of Parliament. To rationalise the work of the Parliament, the MEPs work in thematic committees on the policy files, and form delegations to maintain contacts with the parliaments of third countries. The chairs of the committees and of the delegations, respectively, meet regularly in the Conference of the Committee Chairs and the Conference of Delegation Chairs.

On the administrative side, the Parliament has a Secretariat-General, led by a Secretary-General. It supports the administrative and political work of the Parliament.

How does the European Parliament organise its decision-making process?

Only the Commission has the right to initiate laws. In the ordinary legislative procedure (where the Parliament and the Council have the same powers), after the Parliament receives the proposed law from the Commission (mainly either as a Directive, i.e., a framework law to be implemented with specific laws by the Member States, or a Regulation, directly applicable to the whole of the EU), it assigns it to a committee. Within the committee, a rapporteur is appointed that will prepare the report with the proposed position of the Parliament, to be approved first in the committee and then in the plenary. As the rapporteur belongs to a political group, the other groups each appoint a shadow rapporteur that will follow that file on behalf of the group and negotiate with the rapporteur.

Once the report is presented, amended and approved by the committee, it is submitted to the plenary, where another round of amendments happens before the final vote. If the vote succeeds, that is the position that the Parliament will bring to the negotiations with the Council in the so-called trilogue. It is possible to follow the legislative process and the key actors of the different files via the European Parliament’s Legislative Observatory and via the Legislative Train, which provides up-to-date summaries of the policy positions during the different stages of the approval of the laws.

What are the avenues of involvement for civil society in the decision-making of the Parliament?

As of now, there is not a comprehensive strategy for civil society involvement in the work of the European Parliament. At the political level, after pressure from CSOs, in 2022, the President of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola, has incorporated civil society relations into her own responsibilities, supported by Vice-President, Pedro Silva Pereira. Furthermore, according to the European Parliament’s Rule of Procedures, the Conference of Presidents tasks one Vice-President with organising structured consultation with European civil society on major topics, which, however, has seen little implementation over the years.

The committees regularly organise hearings and workshops for exchanges of views on different policy aspects they are analysing. In such meetings, several times CSOs are invited to provide their expertise, but the process of compiling a list of experts and inviting civil society lacks a structured approach. In the organisation of these workshops, the administrative side of the Parliament (Parliament Policy Departments) and the secretariat of the committees have a role in inviting the experts.

MEPs from at least three political groups can create thematic Intergroups, aimed at discussing specific topics between legislators and civil society. Intergroups are not official parliamentary bodies, but are recognised by Parliament. They are established by agreement between the chairs of the political groups at the beginning of each legislative term. They are generally considered by CSOs to be fairly open for participation and discussion.

Generally, CSOs consider the Parliament as the most accessible of the European institutions, especially in terms of openness of the proceedings in the committees and the plenary. MEPs and some political groups regularly meet with CSOs to discuss their position; however, the follow-up on those discussions is not always clear. Furthermore, difficulties in accessing information on the policy-making process still exist. Some committees provide structured information on responsibilities and ongoing and upcoming work, but this practice is not homogenous. Meetings are web-streamed and accessible from the committees’ websites, but it is not always possible to follow a vote on a legislative proposal as voting lists and compromise amendments are not always made public before the vote.

How does the right to petition the Parliament work?

The right to petition the Parliament is enshrined in Articles 24.2 and 227 of the TFEU, and in Art. 44 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union: any EU citizen or any natural or legal person residing or having their office registered in a Member State has the right to address a petition to the European Parliament on a matter within the Union’s fields of activity and which affects them directly. The petition can be individual, or joint with other people. The petition can be submitted either electronically, on the dedicated website, after the creation of an account, or by post; it has to contain the name, nationality and permanent address of at least one signatory, and be signed. It can be written in any official EU language. Admissible petitions are not published in full, but their summary is available to the public.

If the petition is judged admissible based on the criteria indicated in the TFEU, it is taken over by the dedicated European Parliament’s Committee on Petitions (PETI). There are several possible outcomes: PETI can ask the Commission to start an investigation; refer the petition to another Parliament’s committee, EU institution or executive body for further action; contact national authorities for clarification; prepare a report to be voted on by the Parliament, or first conduct a fact-finding mission in the country concerned; suggest alternative means to redress the issue; put the petition on the Committee’s agenda and discuss it in the presence of the promoters. With an account on the petitions’ website, it is possible to support open, admissible petitions, but that does not influence the outcome of the PETI committee’s deliberations. However, supporting a petition allows you to stay informed about its updates.

Example of successful petition to the European Parliament

In 2016, Mr J.R. (French) filed a petition (No 1088/2016) to the European Parliament on the US’ Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act’s (FATCA) alleged infringement of EU rights and the extraterritorial effects of US laws in the EU. Such a petition prompted the PETI committee to promote a study on FATCA legislation and its application at the international and EU level. The topic was raised in plenary via oral questions to the Commission and the Council. On this basis, the Parliament adopted a resolution on the issue.

Recommendations

- Ensure that the Vice-President in charge of civil society relations becomes a stable figure within the Parliament’s VPs.

- Ensure timely follow-up of the petitions addressed to the European Parliament.

To wrap up

-

The European Parliament has an administrative structure, the Secretariat-General, and a political structure, whose main actors are the MEPs, assisted by APAs.

-

The MEPs are organised in political groups, which have their own staff, are led by one or two (co-)chairs and, together with the President of the European Parliament, lead the works of the Parliament via the Conference of the Presidents.

-

The MEPs work in thematic committees and delegations for the relations with third countries, each of them led by a chair.

-

The key figures in the political and legislative process, apart from the chairs of the political groups, of the committees and of the delegations, are the group coordinators on the different committees, and the rapporteurs and shadow rapporteurs charged by the committees and by the other political groups to follow a legislative file.

-

The Parliament has a VP in charge of organising consultations with civil society and, since 2022, a VP delegated by the Parliament’s President to manage relations with civil society.

-

The Intergroups are unofficial groups that liaise MEPs with CSOs on specific topics.

-

It is possible, individually or collectively, to send a petition to the European Parliament on an issue that concerns them directly, and which is under the remit of the EU’s work.

Materials and resources

Project information

Project Type: Collaborative Project

Call: H2020 SC6 GOVERNANCE-01-2019: Trust in Governance

Start: February 2020

Duration: 48 Months

Coordinator: Prof. Dr. Christian Lahusen,

University of Siegen

Grant Agreement No: 870572

EU-funded Project Budget: € 2,978,151.25